Home Details

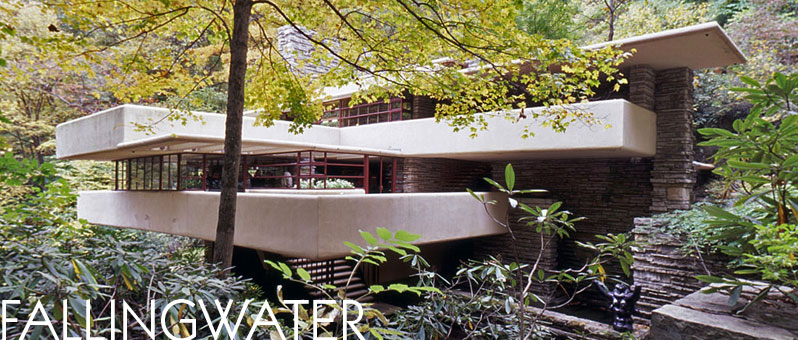

Fallingwater is the name of a very special house that is built over a waterfall. Frank Lloyd Wright, America's most famous architect, designed the house for his clients, the Kaufmann family. Fallingwater was built between 1936 and 1939. It instantly became famous, and today it is a National Historic Landmark.

Why is it so famous? It's a house that doesn't even appear to stand on solid ground, but instead stretches out over a 30' waterfall. It captured everyone's imagination when it was on the cover of Time magazine in 1938.

The Kaufmanns were from Pittsburgh, PA. They owned Kaufmann’s Department Store, a very exciting and elegant place to shop in the 1930s. (Today, it is part of the Macy’s chain). Edgar Kaufmann and his wife, Liliane, had one son, Edgar jr.

The Kaufmanns lived in the city, but like many other Pittsburghers, they loved to vacation in the mountains southeast of Pittsburgh. They could hike in the forest, swim and fish in the streams, go horseback riding, and do other outdoor activities.

Pittsburgh at the time was sometimes called the “Smoky City,” due to the amount of air pollution from Pittsburgh’s steel industry. People who could afford to take the train to the mountains ($1 round trip) relished the chance to breathe fresh, cool mountain air.

The Kaufmanns had a summer camp for the department store employees, located along a mountain stream called Bear Run. When the Great Depression made daily living so hard for so many people, the employees no longer had time or money to come up to Kaufmanns Summer Camp. But Mr. and Mrs. Kaufmann and their son dearly loved the mountains, and decided to make the summer camp their own country estate.

Their summer camp home had been a very small cabin with no heat and no running water. They slept outdoors on screened porches! The cabin stood very near a country road. When traffic became noisy after the road was paved, the Kaufmanns decided it was time to build a more modern vacation house.

They turned to Frank Lloyd Wright to design it for them. At the time, their son was fascinated with Wright's ideas and was even studying with him at Wright's school, the Taliesin Fellowship.

The Kaufmanns, who had recently become very interested in modern art and design, also were intrigued by Wright's ideas, and they asked him to design a new vacation house. They knew that Wright loved nature, as they did, and Wright knew that the Kaufmanns wanted something very special at Bear Run, something only an innovative architect like himself could design. He also knew that they loved the waterfall, and he decided to make it part of the new house.

When the Kaufmanns first looked at Wright's drawings, they were very surprised! They thought their new house would have a wonderful view of the falls. But instead, with the house right on top of the falls, it was very difficult to even see them. But not to hear them! Frank Lloyd Wright told them that he wanted them to live with the waterfalls, to make them part of their everyday life, and not just to look at them now and then.

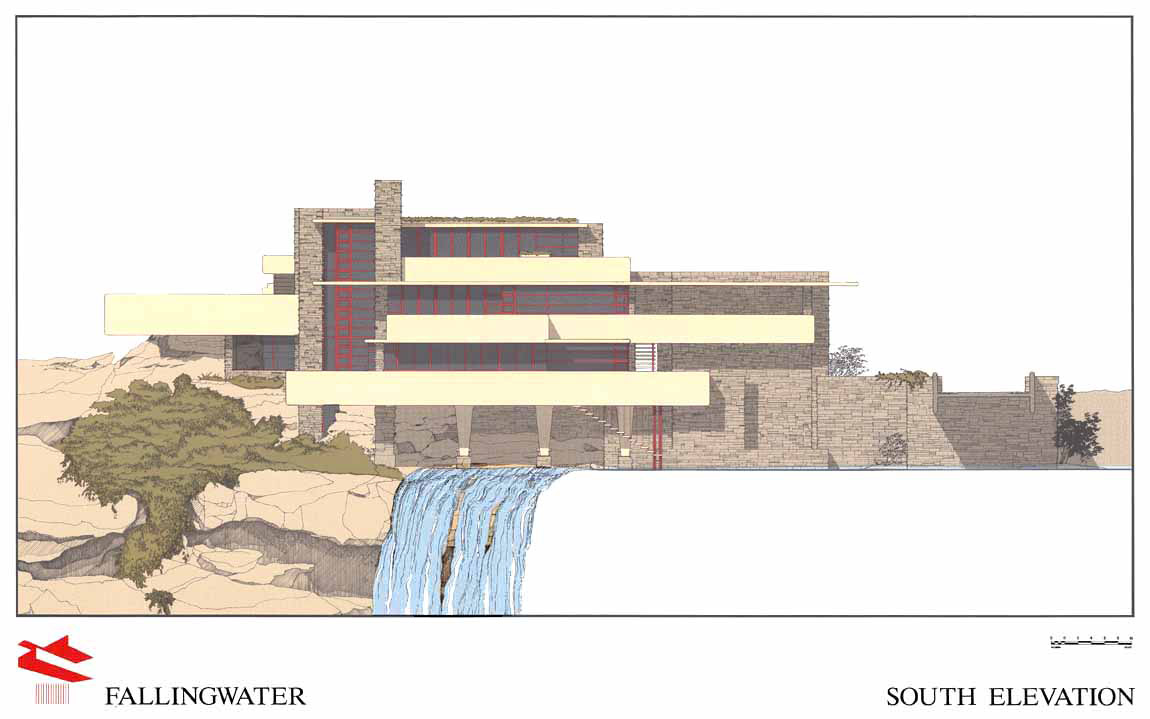

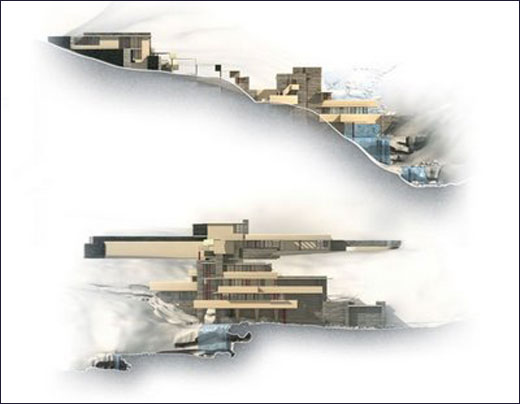

A set of scale drawings of the house were completed several years ago by L. D. Astorino, an architectural firm located in Pittsburgh. These drawings provide a site plan, detail of each level of the house and the guest house and servant's quarters.

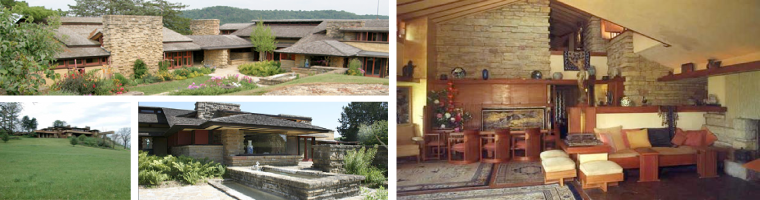

Taliesin (pronounced tæliˈɛsɨn), near Spring Green, Wisconsin, was the summer home of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright began the home in 1911 after leaving his first wife, Catherine Tobin, and his Oak Park, Illinois, home and studio in 1909. The impetus behind Wright's departure was his affair with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, who had been his client, along with her husband, Edwin Cheney. His winter home, Taliesin West, is located in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Some of the buildings designed at Taliesin were Fallingwater, the Guggenheim Museum, the Johnson Wax Headquarters, and the first Usonian home, the first Herbert and Katherine Jacobs house, in Madison, Wisconsin (1936).

In 1940, Frank Lloyd Wright and his third wife, Olgivanna, formed the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, which still exists. Upon Wright's death in 1959, ownership of the Taliesin estate in Spring Green, as well as Taliesin West, passed into the hands of the foundation. The foundation also owns Frank Lloyd Wright's archives and runs a school, the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. The architectural restoration of the Taliesin estate in Wisconsin is under the supervision of another non-profit organization established in 1991, Taliesin Preservation, Inc. The entire Taliesin estate is a National Historic Landmark.

Some $5 million has been spent on the stabilization of Taliesin during the past two decades. Unfortunately, its preservation is "fraught with epic difficulties", because Wright never thought of it as a series of buildings with a long-term future. It was built by inexperienced students, and solid foundations for the buildings were not used. Its future is now in some doubt, and another major fund-raising project is about to begin.

It was submitted for UNESCO's World Heritage List along with the West site but was rejected.

In 2008, the U.S. National Park Service submitted the Taliesin estate along with nine other Frank Lloyd Wright properties to a tentative list for World Heritage Status. The 10 sites have been submitted as one, total, site. The January 22, 2008, press release from the National Park Service website announcing the nominations states, "The preparation of a Tentative List is a necessary first step in the process of nominating a site to the World Heritage List.

The Frederick C. Robie House is a U.S. National Historic Landmark in the Chicago, Illinois neighborhood of Hyde Park at 5757 S. Woodlawn Avenue on the South Side. It was designed and built between 1908 and 1910 by architect Frank Lloyd Wright and is renowned as the greatest example of his Prairie style, the first architectural style that was uniquely American. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on November 27, 1963[4] and was on the very first National Register of Historic Places list of October 15, 1966.

The Robie House is one of the best known examples of Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie style of architecture. The term was coined by architectural critics and historians (not by Wright) who noticed how the buildings and their various components owed their design influence to the landscape and plant life of the midwest prairie of the United States. Typical of Wright's Prairie houses, he designed not only the house, but all of the interiors, the windows, lighting, rugs, furniture and textiles. As Wright wrote in 1910, "it is quite impossible to consider the building one thing and its furnishings another. They are all mere structural details of its character and completeness." Every element Wright designed is meant to be thought of as part of the larger artistic idea of the house.

The Robie House was one of the last houses Wright designed in his Oak Park, Illinois home and studio and also one of the last of his Prairie School houses. According to the Historical American Buildings Survey, the city of Chicago's Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks stated: "The bold interplay of horizontal planes about the chimney mass, and the structurally expressive piers and windows, established a new form of domestic design." Because the house's components are so well designed and coordinated, it is considered to be a quintessential example of Wright's Prairie School architecture and the "measuring stick" against which all other Prairie School buildings are compared.

The house and the Robie name were immortalized in Ernst Wasmuth's famous 1910 publication "Ausgefuhrte Bauten und Entwurfe von Frank Lloyd Wright" (a.k.a. "The Wasmuth Portfolio"). This publication featured most of Wright's designs, including those unbuilt, during his Oak Park years and brought them to the attention of European architects of 1920s, especially students of the Bauhaus school in Germany and the De Stijl school in Holland. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe among other great 20th Century architects, claimed Wright was a major influence on their careers.

The architectural significance of the Robie House was probably best stated in a 1957 article in House and Home magazine:

During the decades of eclecticism's triumph there were also many innovators--less heralded than the fashionable practitioners, but exerting more lasting influence. Of these innovators, none could rival Frank Lloyd Wright. By any standard his Robie house was the House of the 1900s--indeed the House of the Century.

Above all else, the Robie house is a magnificent work of art. But, in addition, the house introduced so many concepts in planning and construction that its full influence cannot be measured accurately for many years to come. Without this house, much of modern architecture as we know it today, might not exist.

In 1956, The Archectural Record selected the Robie House as "one of the seven most notable residences ever built in America." In 2008, the U.S. National Park Service submitted the Robie house, along with nine other Frank Lloyd Wright properties, to a tentative list for World Heritage Status. The 10 sites have been submitted as one entire site. The January 22, 2008, press release from the National Park Service website announcing the nominations states that "[t]he preparation of a Tentative List is a necessary first step in the process of nominating a site to the World Heritage List."